Archive

The Eyes Wide Open Election, Part 4: Psalm

[continuing a series on the election that was. To read “Part 1: Acknowledgement,” click here. To read “Part 2: Resolution,” click here. And to read “Part 3: Pursuance,” click here.

“In the bank of life isn’t good that investment which surely pays us the highest and most cherished dividends?”

– John Coltrane, notes to “A Love Supreme”

The confidence with which each side of the American political divide presents themselves as righteous and good is for many people one of the great turn-offs of our political discourse. Perhaps that’s why Trump, his party and his supporters now try to have it both ways: presenting as God’s chosen messiah (“I was saved by God to make America great again“) while also reveling in villainy, in cancellation, in being assholes who hurt people – but assholes on your side. Self-consciously positioning as the opposite of that – on the side of democracy, on the side of maliciously-targeted groups – has produced limited success for Democrats. I’m not about to suggest that Dems attack the same people, or embrace authoritarianism. We should continue to be, for lack of a better term, the good guys, and let Trump and his flock be the villains/false idols they so desire to be. But by itself, we now know that won’t be enough. So we need to find another way to reach people.

We’re in the midst of a substantial political realignment along educational lines and along levels-of-engagement lines. I generally believe that Democrats will come out on the short end of this realignment, but will achieve intermittent electoral success should Trumpian chaos leave voters short-tempered in lower-turnout elections. I could see the former changing if a Dem breaks through at the national level with a message outside the usual left/center-left dichotomy into less-charted territory relating to how screens and social media platforms and artificial intelligence have frayed, and will fray, our societal bonds. This terrain maps less neatly onto our political divides, meaning it offers the chance to build new coalitions.

To everything there is a season, and in this season it seems more practical for me to read, think and write about past realignments and those presently underway than to do the hamster-wheel work within the party. That’s not to say the latter is unimportant – but one must understand what they have available to offer at any given time. Pretending that everything is normal and we just go about our business with the same political strategies and structures as before? That seems naive. I need to go away and dream it all up again, to quote Bono back in 1989. I’ll very much still be following elections and commenting on them – but on the ground, right now, it falls to someone else to do the party work and the voter contact and all that. When I’ve had some time to dream up something new and find myself having something to offer, I’ll get back to that kind of work, and I hope the Democratic Party will be ready when I am.

***

These four pieces are the most forced things I’ve written in a long time. I’m not sure how I feel about them. I suspect I will not look back favorably on them for their style or construction or most certainly their titles, and I suspect I’ll be annoyed most of all at their lack of insights. But at least I acknowledge a lack of insight, at a time when so many Democratic electeds and “leaders” would have us believe they have the answers when in fact they’re stunned, directionless and simply waiting for something to happen.

The Eyes Wide Open Election, Part 3: Pursuance

[continuing a series on the election that was. To read “Part 1: Acknowledgement,” click here. To read “Part 2: Resolution,” click here.]

It is one thing to acknowledge the world as it is, another to evaluate competing narratives around it, and another, far more challenging thing to determine where I think the Democratic Party goes from here. I think there are a few obvious elements when it comes to strategy and infrastructure:

- Playing to the cable news audience is a fool’s errand. Personally I’d rather news just be, you know, news. There’s room for talking heads on cable news just as I believe there’s room for editorial pages in a newspaper – but the ratios ought to be very different than they presently are. But if cable news is going to operate the way it currently does, and include an ideological bent, I don’t think the Democratic Party or its officials need to play along. The MSNBC crowd does a better job of sharing facts with their viewers than, say, Fox News. But it does little to encourage viewers to understand the electorate around them, and every minute Democratic figures spend talking to high-info base voters is a minute that could have been spent trying to reach people who oscillate between engagement and non-engagement, or the even smaller portions of the electorate that splits their tickets or swings between parties from one election to the next. This seems like an incredibly obvious point, but it’s stunning how much time Democrats spend talking to their most fervent supporters at the county, state and national level. It’s stunning when you watch it up close in local politics, and stunning when you watch it from a distance on the national scene.

- A lot of folks seem to understand that the political consultant class adds little. Coin flip national elections have become the norm, and we win them about as often as we would a…coin flip. It was clear in 2016 that Democrats faced softness with white working-class voters, and Biden barely improved on Hillary Clinton’s margins with these voters in 2020. It was clear in 2020 (and every subsequent year) that Democrats now also faced softness with Black, Latino and Asian working-class voters, and Dems went backwards with these voters in countless elections in 2021, 2022 and 2023. Everyone knew, in other words, that Democrats faced a challenge in reaching working-class voters across the demographic board in 2024. And yet the consultants paid to win elections could not develop a plan to turn the tide. The reality is campaign fundraising for federal elections is easier than ever, and the consultants get paid – win or lose. And then they usually get hired again. So a lot of our supporters’ hard-earned money is going to people who spend December vacationing on a beach whether they’ve won or lost the previous month. Democrats need to re-assess who actually adds value when it comes campaign infrastructure. This, again, seems like an incredibly obvious point. And yet it doesn’t happen. Professionals who can make campaigns more of a turnkey operation likely raise the floor in electoral performance, but I’m worried it lowers our ceiling and leaves us dependent on how the national-level coin flip lands. Maybe Democrats need to run candidates who devise their own bespoke strategies based on their feel for their communities – and if they don’t have that feel, if they have nothing distinctive to offer on their own without having consultants craft it for then, they need not to run.

- In a time of low social trust with lower contact rates from phonebanking and doorknocking, I’m not sure that the classic campaign field tools should be relied upon as much. It’s not 2008 or even 2018 anymore, but you wouldn’t know that from the endless speeches from well-meaning organizers about how we need to be pounding the pavement. That said, I remain interested in well-meaning organizers who are immersed in a community for several cycles and can develop a feel for what works and what does not. I’m certainly open to returning to and expanding the Dean-era 50/50 state strategy. I’m interested in moving away from the “gig economy” model of organizing toward something that provides living wages, benefits and stability for a larger number of organizers than we’ve previously done in our allegedly pro-labor party.

Messaging, policy and strategy present questions – with much less obvious answers – of how to pursue electoral success in a second Trump term.

- I’d start by pulling back from left/right or economics-versus-culture wars dichotomies and ask how Democrats assess the wider societal dynamics that got us into the Trump Era. Democrats are losing the war for attention, in part because the party styling themselves as overturning the present order are going to have the upper hand in winning eyeballs. There’s a lot of discontent in the post-pandemic world, and it’s easer to tap into that than to defend an unpopular status quo as Democrats found themselves doing in the Biden years. But there’s a larger question to be asked about the attention economy and its impact on how people view contemporary life. I’m always saying that this timeline we’re in just doesn’t “feel right” – and screens and social media and the homogenizing of American communities might have something to do with that feeling. I think there’s room for someone to demand that we pump the brakes on our screen-induced devolution and to resist the mega-corporations at the core of that decay. Ezra Klein recently discussed this idea on his podcast with guest Chris Hayes, arguing that aspects of this sensibility are widespread and that the next really successful national candidate – from whichever party – might be the one that taps into those feelings. I tend to agree. The transcript is worth a read, but here’s the passage I found most resonant:

- I’d widen that brake-pumping – or preferably, outright reversal – to AI’s growing infection as well. And lest you think I’m falling into the trap I often lament and suggesting that a candidate who conspicuously and conveniently echoes my own beliefs is the one who’ll carry the day, let me offer a couple of caveats. I have no idea if this narrative will produce electoral majorities. But I think there’s a space for it that someone would be wise to fill, and a wayward Democratic Party that frankly isn’t doing any other big-picture projects ought to do it. And I’m being consistent: I’m not spending time in this space suggesting that Democrats focus heavily on foreign policy concerns that are of major interest to me…and not too many other folks. I predicted in 2002-03 that following up our Afghanistan nation-building efforts with an invasion and occupation of Iraq would not only become massively unpopular (it did) but would launch a generation of isolationism in response, uniting Americans on the political right and left against overseas involvement. It did, with Trump’s America First agenda reaching escape velocity as a result. It is damn near impossible to have serious discussions about international security, inside our party and among the wider polity. That frustrates me to no end, but I’m not going to suggest that the electorate is willing to re-engage on foreign policy and national security outside of yelling at each other in an often-reductionist fashion about the existential threats facing both Israelis and Palestinians.

I’d like to feel more confident that something like what I’ve described above is at hand, but I’m still seeing too many Democrats engaging in tired defenses of Biden’s political strategy or arguing that we just have to wait for Trump to mess up, and then we’ll be ok. The latter might produce some midterm wins, but it’s not clear to me that it won’t be too late at that point to roll back a lot of damage in both policy terms and to small-d democratic governance. And it’s not clear that it will create national majorities in 2028 and beyond.

The Eyes Wide Open Election, Part 2: Resolution

[continuing a series on the election that was. To read “Part 1: Acknowledgement,” click here.]

Democrats are doing the usual Democratic thing: analyzing the defeat and suggesting changes.

That’s healthy, in theory. It’s what normal political parties who assume their viability is more or less tied to the popularity of their specific policies would do. There’s a catch, though: just as predictably, the ideological bent of too much of the Democratic post-mortem discourse has been eyeroll-inducing. The party’s left flank argues that if only Dems embraced more leftist positions, new voters would stampede to the polls in support. It’s probably worth noting that Bernie Sanders1 and Elizabeth Warren2 received fewer votes than Kamala Harris in their respective states – though I’ll acknowledge those states are not demographically representative of “swing” states. Centrist Dems outran Harris in some of the toughest Congressional seats that Democrats held (see ME-2 and WA-3 for two good examples). At the same time, centrists argue that Dems must tack to the center to win back voters who have drifted to the GOP…but they mainly focus on what not to talk about rather than an affirmative set of policy prescriptions. Voters quite clearly signaled in the years leading up to this election that their primary concerns were inflation and immigration, so after-the-fact prescriptions about rejecting “wokeism” or embracing Medicare For All do not ring true – even if I tend to agree that the language Democrats use around certain issues is unhelpful, and agree wholeheartedly that Democrats would be wise to attack (legislatively as well as rhetorically) consensus evils like the outrageous, patient-killing tactics employed by private insurers.

Republicans are doing the usual Republican thing: exalting in victory and over-claiming their mandate. They had Sen. Bill Haggerty of Tennessee on Sean Hannity’s show shortly after the election declaring that “Trump certainly has a mandate that we’ve never seen before.” Countless Republicans have echoed the sentiment. In reality, Trump’s margin of victory ranks quite low in terms of the popular vote, with his vote share coming in under 50% and his lead over Kamala Harris ending up at less than 1.5%. That is the seventh-smallest popular vote margin since the Civil War. It’s wider in the electoral college, which is obviously the ballgame: but a 1.5% shift in the three closest states gives Harris an electoral college win, so we’re still not talking about big margins. Trump won, and no one disputes this. But the idea that it’s a large, historic mandate is confounded by simple math. His mandate in mathematical terms is nowhere near Biden’s, or either of Obama’s; even George W. Bush’s 2004 win came with a considerably larger popular vote share. But many media outlets are currying favor with the incoming administration and Congressional majorities. We’ve seen the settlements with Trump over lawsuits, which feel a bit like bribery. And they’re eager to be seen as ratifying voters’ choices and perhaps to attract Trump voters back to legacy media outlets they’ve long since abandoned. So the tenor of coverage presents an incongruously imperious political position for a party whose presidential candidate won narrowly and is currently polling five points underwater, and whose House majority is the smallest any party has enjoyed since 1931.

People who spend their time dismissing parties and elections as a means of improving the world are suddenly finding out that those things do in fact matter.

One can find folks online – and definitely in my own real-life circles – saying, “wait, Democrats prophesied doom if Trump won – why are they carrying on now like everything is normal? Heavens, why…why aren’t they DOING SOMETHING about it?” Folks, this isn’t hard: they argued the election was critically important *because* of the lack of things you can do when all the guardrails have been stripped away, which already happened: the Supreme Court has rolled over for Trump. His party, which now controls both house of Congress, long ago rolled over for Trump. Yeah, they’ll draw the line at a Matt Gaetz attorney general nomination, but not much else. What do you want Democrats in Washington to do? Chain themselves to desks? Get arrested? Your mileage may vary, but I’m not interested in performance politics right now. As Jonathan Van Last notes, most of the remaining power of resistance is in the hands of bureaucrats – the so-called “Deep State” – to work quietly – unseen – to delay harmful actions. In sum, Democrats said the election had existential stakes precisely because the last eight years have eroded the options to resist.

That being said: sure, I would rather Biden have dispensed with now-obsolete niceties like posing for pictures with the president-elect – especially if by pardoning his recidivist son, he was going to make politics harder for those of us tasked with carrying the torch for this declining, atrophied party in the aftermath of his presidency. I would rather Democrats have repaired any number of long-standing structural problems involving special counsel authority, ethics for federal judges, and background checks for cabinet appointments, to offset some of the erosion in guardrails in the Trump era. I would rather Senate Democrats have use their appointment powers to maximum effect in the lame duck period, but former Democrats Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema are a limiting factor. And I’d rather responsible non-Democrats like Christopher Wray not resign as head of the FBI and instead make Trump actually fire him, so as to put more cards on the table for more people to see. But none of these individuals are behaving responsibly or effectively. They’re confused and capitulating. Caveat: David French offers another take on Wray’s decision.

Even as I write this, the Democratic leaders in the House and Senate are responding in slow-motion – to the extent they’re responding at all – to Elon Musk’s friends potentially taking over payment systems at the Department of Treasury, or the firing of over a dozen prosecutors at the Department of Justice in retaliation for previously investigating Trump. It may be that to truly change the political dynamic, you have wait for Trump, Musk & Co. to do something that breaks through to people. But you still have to provide your own supporters with something to grasp onto to take advantage of those eventual mistakes.

- my preferred candidate in the 2016 primaries – but it’s complicated and I came to regret that. Whatever her faults, Hillary Clinton deserved better in those primaries, and obviously in that general election. ↩︎

- my preferred candidate in the 2020 primaries – after which I had to reckon with the reality that I am not particularly representative of the vast majority of the population. ↩︎

The Eyes Wide Open Election, Part 1: Acknowledgement

My thanks go out to a longtime friend for describing the “eyes wide open” nature of this election. I think he nailed why this result hits the way it does for those on the losing side – even if all available data showed defeat was as likely as victory, if not more so. This one lacked the newness of Trump’s 2016 campaign; it lacked any subtlety. Whether one believes his talk of mass deportations and retribution against political enemies or not, he campaigned loudly and clearly on these items and gained support along the way – ending up more popular than at any point previously, albeit still underwater with the American people.

In 2016, one could plausibly argue that his rhetoric was a means to an end, and that he would govern differently. Even in 2020, one could still argue that there was a limit to Trump’s self-aggrandizing behavior – though unlike me, my mother was among those who correctly anticipated he would not engage in a normal, peaceful transfer of power. To take one piece of a much larger puzzle, Trump’s campaign this time not only dismissed culpability on his part for the violence and vandalism that took place on January 6, 2021 – he pledged to pardon those who carried it out. We once again have a president who through his rhetoric and actions expresses a view of the presidency as a vehicle to enrich allies and punish enemies, a Supreme Court that has ruled he cannot be held criminally liable for any actions he takes as president, and an ever-growing base of support for him: from just under 63 million votes in 2016 to 74 million in 2020 to a little over 77 million in 2024. I’m not particularly exercised by claims that the media failed to properly elucidate the stakes of this election, or that people “voted against their own interests.” Those 77 million people aren’t making their decisions based on New York Times and Washington Post headlines. Nine years into this experience, most voters know what kind of person and president we’re dealing with here, and enough of them have gauged it’s in their interest to back him that he keeps increasing support both in raw numbers and in his share of the electorate. To the extent they anticipate consequences to Trump’s policy plans and political project, they foresee those consequences helping and hurting the “right” people. Their eyes are wide open, and our eyes ought to be as well.

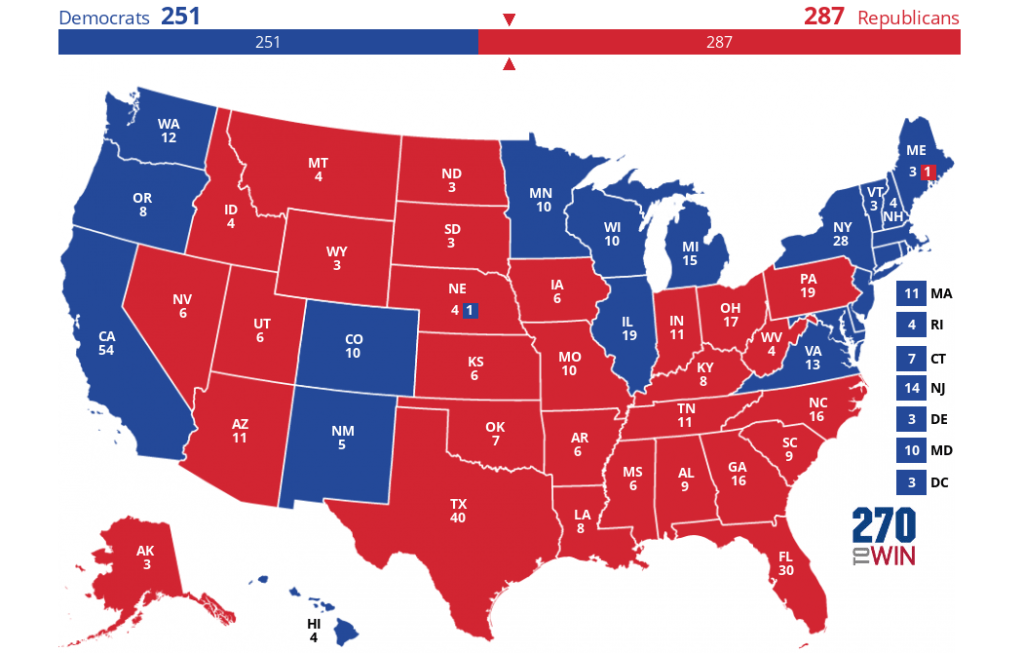

I suppose mine were, not that it alters my emotional response to the results. I felt by March of this year that Joe Biden was headed to defeat. His State of the Union performance was pretty solid and stopped the bleeding for a bit…only for the worst debate performance in modern times to re-establish the tenuousness of his position. After weeks of stubborn deliberation, he finally stepped aside in late July so Kamala Harris could make it a ballgame – and she did. That said, she was unable to open comfortable leads in any of the swing states. When our trio of analysts here at WTM started our Race Ratings spreadsheets in September, I had Trump winning the electoral college, 281-257. Over the next month, I expanded his lead in my ratings to 312-226 as I moved Michigan, Nevada and Wisconsin into the Trump column. As the final weekend of the campaign drew to a close and Harris appeared to be finishing stronger, I moved MI/WI back to Harris, leaving Trump winning 287-251 on my final map.

As I noted at that time, the “official” WTM map showed a Harris win – because my optimistic colleagues outnumbered me. But from March through November, I rarely if ever had Harris reaching 270 electoral votes. I could see arguments for Harris outperforming her polling – in particular, I thought her campaign infrastructure and closing message were stronger than Trump’s outsourced, fraud-riddled voter contact efforts and his at best unhelpful rally at Madison Square Garden that highlighted the cesspool that orbits around him. But while that path was plausible, I believed throughout the fall that Trump had advantages that could and probably would narrowly offset those deficiencies. And lo, they did.

***

If there’s one thing the last few months have shown us, it’s the limited value of immediate post-mortems following an election. For one thing, they start much too early. 10 pm on Election Night? Too early. Late November? Still too early. Even setting aside the fact that truly granular, enlightening analysis requires a look at the voter file to see who actually showed up to vote where, it took a while to get final raw numbers. Some states count efficiently and others do not; some states have generous ballot-curing laws that allow voters to correct mistakes on their mail ballot envelopes so that election administrators can confirm they are legally cast and subsequently count them. Various tranches of votes get counted on varying timelines in each state, resulting in a somewhat picture on election night than once everything is counted weeks later. Trump’s share of the vote was around 51% on election night; it ended up below 50%; he finished a point and a half ahead of Harris with the seventh-closest popular vote margin since the Civil War. Subsequent attempts to paint the election as a landslide are mathematically bizarre, ahistorical and reveal insecurities on the part of both the party advancing that notion and the stenography-oriented media outlets echoing it. But two things can be true at once, and it also the case that losing an election – however close – to a candidate with a demonstrated preference for Orban-style illiberal democracy is an earthshattering defeat that reveals something about both the electorate and the defeated party.

It’s also now clear that in some of the cities and counties where Trump’s share of the vote went up substantially, he made little to no gain in raw votes: in those cases, the changes are due to drops in the raw vote for Harris relative to Biden. Note that none of that changes the reality that Trump gained vote share in every state and made notable gains in Democratic heartlands – there are indeed plenty of urban precincts where Trump gained in his raw vote total over 2020, contributing to him growing his raw vote total by more than three million nationally.

There are illuminating elements to this defeat. A couple weeks before the election, I mentioned to WTM collaborator Matt Clausen that losing the popular vote – as seemed a real possibility to me – would at least be clarifying for Democrats in some fashion. And indeed that popular vote defeat has come to pass. So this isn’t 2000 or 2016, where Democrats could point to the popular vote and say “but for the anachronistic electoral college, we’d have won.” Or point to an unfavorable court ruling, like 2000. Democrats have to reckon with the reality that while this loss was close, it was also comprehensive at both the presidential and Senate level. Comprehensive losses require comprehensive solutions – turnout played a role in this defeat, but so did persuasion. And those two concepts are more intertwined than some Democratic operatives are inclined to believe. George Packer makes note of this in his recent piece on “Democratic delusions” that can now be retired.

I think there is illumination to take in terms of campaign elements and strategy as well. The Harris campaign was better-funded and it had a stronger traditional ground game, as Matt and I wrote about on this site at different points. These either didn’t matter or didn’t matter enough. Or maybe the ground game was just bad. My understanding is that while the Harris campaign exceeded the nearly non-existent door-to-door effort of 2020, and had more offices in more places than Clinton in 2016, Dems were still a long way from having an organized campaign on the ground in every county in each presidential swing state. The 50-state strategy days of 2008 are a distant memory even though Democrats are quicky to point to how outgunned they are in the media environment. Every state, every county: if Dems believe that sustained, in-person voter contact is crucial in a world of local news deserts and polarized national media, they need to actually invest in it. For our part here at Within the Margin, we tend to think that simply demonstrating commitment to reaching every corner of the map itself addresses the common claim that Democrats are too far removed from too many voters and opens a door to dialogue.

A Tale of Two Maps: Presidential Edition

There’s a scene in the film Margin Call where an investment bank CEO played by Jeremy Irons observes that his role boils down to knowing what the “music” of the financial markets is going to sound like over time. As his company faces a financial crisis, he notes that at that moment he doesn’t hear the music at all – not a thing.

I’ve always liked that metaphor as it relates to those of us who have engaged with elections and campaigns. The three prognosticators at WTM have been around them as campaign staffers, advisors, volunteers, and close-up observers for a long time now. I think that I’ve personally gotten a lot better in recent years at hearing the music of a campaign and tuning down the inherent optimism that comes from having a rooting interest and in some cases being involved in the campaigns beyond simply voting for a candidate. 2022 was something of a triumph in the other direction, in that I knew as the campaign unfolded that the prevailing narratives were off and the presumed “red wave” was not actually forming. Yet I recognized that closer to home in New York it actually would be a redder year, though I missed the severity. I think in 2023, I could tell the way the music was playing in my home county: I anticipated flipping one county-wide seat, gaining three county legislative seats, and losing one. And that’s what happened, though Dems did even better than I expected in town races. All in all, good signs that I wasn’t getting lost in the cacophany of the miracles I was rooting for, while still seeing the victories that were achievable.

For the first six and a half months of 2024, the music I was hearing said the same thing as much of the polling: Donald Trump was in a considerably stronger position than 2020, and Joe Biden was in a vastly worse place…and steadily slipping. The fundamentals of consumer sentiment and an unpopular incumbent seemed to be feeding into each other. Biden couldn’t seem to create his own political weather, and swing voters’ skepticism was hardening. His State of the Union performance in March seemed to show he could still put together a solid set piece. He could still deliver a narrative and be quick enough on his feet to engage in repartee with opposition hecklers. It wasn’t a game-changer, but it seemed like it could arrest the slide. But June’s debate with the former president proved otherwise, and the bottom really began to fall out. An electoral map where Trump approached the electoral collage numbers of Barack Obama or Bill Clinton now seemed possible. That started to change when Biden withdrew from the race and Kamala Harris executed an incredibly successful campaign launch. Polling improved, of course, but something else did too: a second song was now playing alongside the other one. For all that Joe Biden’s record on domestic policy includes major wins – infrastructure investments, the CHIPS Act, prescription drug prices, a surprising “soft landing” where inflation came down without a recession – it didn’t feel like there was narrative heft behind it. There was no music to it. The Harris launch unleashed a torrent of optimism among Dems who knew a change was needed to a candidate who could make an affirmative case and put in the work – the rallies, the countless media hits, and, yes, the debate performance – needed to win this election.

But that didn’t change that the other music was still playing. And so for the final months of this campaign, it has hasn’t been that I can’t hear the music, like the Jeremy Irons character…it’s that I’m hearing two very distinct pieces of music at once. To torture the metaphor a little bit more, maybe the discordant, chaotic piece of music is just a little bit louder than the organized, cautious, hopeful piece.

People smarter than me have correctly noted that in such a tight election, it’s going to come up Trump’s way at least 45 times out of a hundred, and Harris’ way at least 45 times. It’s the other ten times that are harder to predict. That’s one way where it differs so much from 2020, when Biden’s polling lead was enough to withstand a historically large polling error – and indeed we got the large polling error, and Biden still got the win. This time, a normal polling error in either direction would give either candidate a fairly comfortable win. And there’s not much reason to believe the polling error would be in Trump’s direction, like it was in 2016 and 2020, as opposed to the Dems’ direction like it was in 2012 and various 2022 midterm races.

But as I said above: I think one set of music is playing loud enough to win just a little more often. And so we get this map from me:

It’s not a massive Trump win. It’s fewer electoral votes than his 2016 victory. But it’s enough to win. Let me hit on the seven swing states, and then make another couple of observations, and then show you the Matt/Jim map.

- Michigan: This is a state where Harris has led more often than not and where we get a double-whammy in terms of ground game: the Harris campaign is better organized than Trump’s turnout operation nationally, and in Michigan the state Democratic Party is effective whereas the GOP is in disarray. Inflation has hit the Midwest to a lesser extent than other parts of the country, and the polling in non-swing Midwestern states shows Democrats holding up well. Even if it’s effectively a polling tie, the combination of late-breakers with less of an economic argument against Harris plus the strong organization on the ground gives her the edge. I think Arab-American abstentions or third-party votes will be impactful, but that’s priced into polling.

- Wisconsin: Most of the same factors as Michigan, but the disparity in organizational effectiveness among the state parties is even greater. Ben Wikler’s Wisconsin Dems are very good at what they do in statewide elections, and I suspect that provides an extra edge – along with the fact that so much of their coalition is high-propensity voters. As with Michigan, Ron Brownstein has noted that the share of white working-class voters has dropped here since 2020, and I think that puts Harris in a good place here despite how incredibly close the Badger State was four years ago.

- Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania has largely been fought to a draw. I think the attention given to the party registration changes here are a bit overblown, as Democratic registration trends still look solid in the largest and fast-growing counties. I suspect Trump’s Madison Square Garden rally has set back or even reversed any inroads he was making among the state’s large Puerto Rican community. But I also think the mood music in the Keystone State has been problematic in terms of election administration stories in Bucks and Lancaster counties that contribute to confusion and the general sense among Trump-curious voters – however inaccurate – that the system disadvantages him somehow. Of the states I have Trump winning, this is the one where I’m least confident, by far – and with 19 electoral votes it’s the difference on my map between winning and losing the entire election.

- North Carolina: There are reasons to believe Harris is finishing strong here, and there may also be some folks in red-leaning counties who are unable to prioritize voting while digging out from the horrible damage wrought by Hurricane Helene. I hate to even raise that in a horse race electoral context. But even accounting for that, this is a state Trump won in 2020, and making up a point and a half in a country that seems, on the whole, a little bit more Republican than four years ago is a big ask. I think North Carolina will be even closer than 2020, but Trump holds on.

- Georgia: I expected Democratic momentum here to continue into the 2020s, given the favorable demographics of a fast-growing, diverse population with a lot of college-educated transplants. But while Harris has made up considerable ground here since replacing Biden atop the ticket, I can’t ignore that she continues to trail and that the campaign seems to have given more time down the stretch to North Carolina.

- Nevada: As the Obama/Reid era of Democratic dominance fades from view in Nevada, elections have been getting tighter and tighter here. We’re talking about a state that was hit harder than most with price increases, with a population heavily tilted toward working-class, often transient people – including, it seems a lot of people fleeing California’s housing shortages and even higher costs. However misplaced the blame for high prices might be, the reality is they’re feeling it. Coupled with Trump’s inroads among Latino men, and the early/mail voting numbers in the only state where we can actually divined something from them, and I think Trump edges it. Harris has a shot; Nevada elections guru Jon Ralston picked her to win by a few tenths of a point based on his intricate analysis of the turnout prior to today. But I think he’s expecting a slightly better election day turnout than we’re actually going to see in a state where voters feel like they’ve faced too many challenges in the last four years.

- Arizona: Like Georgia, I expected Democratic fortunes here to continue to shine post-2020. And in fact, Democrats won three major contests here in 2022: flipping the governorship and Attorney General while holding onto Secretary of State. But like Nevada, the combination of higher inflation than much of the country and the influx of conservatives from other states makes it difficult to see what Harris’s path would have been – and polling has consistently shown her lagging accordingly, though less than Biden had been here.

I can articulate countless arguments to the contrary:

- The organized, professional Democratic turnout operation reaches more of their low-propensity voters than Trump’s, and is worth more on the margin even than I’m predicting above. Matt emphasized this in the piece he published for the site overnight. Check it out here.

- A Dobbs effect that pollsters (besides Ann Selzer at the Des Moines Register) are missing, where women make up an even larger and more Democratic share of the vote than usual, perhaps with crossover support from Republican women – though pollsters largely saw this in 2022, so it would be unexpected for them to miss it now,

- Or the inverse: the “manosphere” voters who the Trump campaign is relying on are generally low-propensity voters and that’s always a risky bet. If they don’t show up in substantial numbers – and they certainly aren’t getting doorknocks or phone calls nearly the way Dem voters are – that gives Harris more margin for error.

- Haley voters (or some other kind of Trump-skeptical Republican – support Harris in larger numbers than pollsters are seeing. The Trump campaign certainly didn’t make much use of her offers for help down the stretch. What carries more weight – her dog-bites-man endorsement of him, or the anger toward Trump felt by those who voter for in the GOP primaries – often in sizable numbers even after she had exited the race?

- Harris has shown signs of making up some of the ground Biden had lost with Black and Latino voters. If she gets something like 2020 turnout and 2020 margins – in defiance of polling and metrics – she’d be in great shape.

- Maybe polls in general have been too Trump-friendly as various surveys attempt to avoid a repeat of their 2020 misses. Smarter folks than I have pointed out the issues with weighting to re-create something like the 2020 electorate, and there’s been so much herding in the final weeks where pollsters just show a tie or a one-point lead in state after state because they don’t want to stand out or be assailed for a miss. Of course, they could also be herding away from a clearer Trump win – though there’s less reason to assume that given that pollsters are trying to correct that.

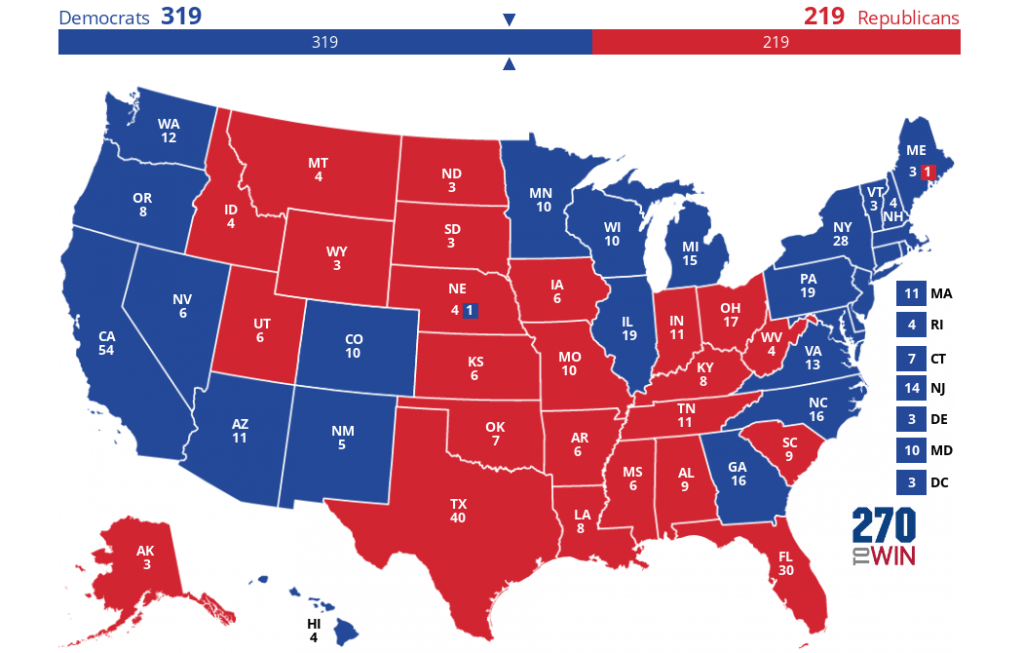

And countless others I’m forgetting. Those reasons and more are why the other two-thirds of the Election Ratings posse here at Within the Margin are much more confident of a Kamala Harris victory. Jim and Matt have her sweeping the swing states, for 319 electoral votes:

I like that map quite a bit, and I can see where they’re coming from. We’ve been talking this through for months, after all.

Let’s see what happens. It feels weird to leave it at that given the stakes – but that’s a very different conversation. Thank you all for reading. We’ll see you in the coming days.

The Fundamentals Were Never with Trump

Oh, hey, it’s Matt. So, it’s been kind of a while since I wrote here (like a long while). I apologize, but I have been doing stuff on the sidelines like the WTM ratings with Brian. As the end of the 2024 Cycle is fast upon us, let’s explore what I think is the most and yet least controversial take one could have at the end of a cacophony of punditry and pontifications across the political spectrum (we at Within the Margin, withstanding): that the fundamentals of this race never favored Trump. Whether you start the clock on the evening of January 6th, 2021, or the dreaded afternoon of June 24th, 2022, the bell tolled for Donald Trump’s chances of winning. It is through the sort of manufactured luck that typically gets you thrown out of profitable casinos that this character kept drawing inside straight after inside straight to “luck” his way to the final table. We can only hope that this table spells the end of him and the beginning of the end of the vile ideology that will still need to be electorally exterminated over who knows how long.

Now, let me state unequivocally that Trump’s re-nomination was never in doubt. From January 6th to his official clinching earlier this year, Trump was never truly challenged for the party’s apparatus. Ronna McDaniel remained as HIS RNC Chair (until she conveniently wasn’t); his word carried weight in State Party Committee selections and the overall composition of the RNC. It’s effortless to ice out everyone when you control the infrastructure. As much as the Ron DeSantises or Nikki Haleys of the world thought there were ashes out of which to rise, they were never seriously going to challenge for the “crown.” From his announcement, the nomination was his.

It is easy to argue that prior to President Biden’s exit from the race, everything favored Trump. On the Economy, and with the double-haters likely favoring the challenger, this would be superficially true. On the economics question, there’s a lot to unpack given the overall tax cuts from 2017 and their long term effects, the effects of the pandemic, and the long recovery from it in terms of general affordability. The economy is still something of a pain point, but one side declaring a tariff through extralegal if necessary means is sort of self-disqualifying. There was also a burst-through on immigration (a position purposely poisoned for the SOLE purpose of the election, most egregiously by Donald Trump but with huge assistance from Greg Abbott and Ron DeSantis) as well. But let’s pull the lens back from the simple narrative of an unpopular incumbent in trouble due to the economy.

Fundamentally, Donald Trump wasn’t running a political campaign. He was using the RNC and his campaign as a slush fund vehicle to underwrite his legal issues. Across every case, he was utilizing the campaign and the RNC to fund his legal expenses. They were not building out campaign infrastructure. They weren’t focusing on voter persuasion and active voter mobilization and registration. Now, it can be argued that these were being taken on by other groups and therefore not a need for the RNC and the Trump campaign…but that’s not a guarantee. Look no further than the “GOTV” of Elon Musk’s America PAC. Prior to America PAC’s actions, the RNC had Turning Point USA running their Field operation and doing… what, exactly?They were not dedicating time in the states that were going to be the tipping point or that sat a knife’s edge. At no point were these vehicles benefitting the campaign. Finally, the registration efforts…we’ll see how effective they were. In the end, there was no effort to run a campaign in the traditional sense; tons of money came into the Trump coffers, and the RNC, but most of it went right back out.

Next, Trump never addressed the elephant he happened to drop into a room by way of the Dobbs Decision. It is certainly my hope that June 24th of 2022 will mark the beginning of the end for the era of Trumpism and that while beating him at the ballot box one last time may be sweet, the ideas and ideals fester. Dobbs was the bomb that changed the supposed “Red Wave” of the 2022 midterms. It kept Democrats in play to keep the majority in the Senate and to only lost the House by a handful instead of 20 seats. Dobbs created that. It’s impossible to say if Dobbs was the major contributor to the first special election after it came down (the Nebraska 1st on June 28th of 2022), but it possibly played a role there and definitely played a role in a number of other special elections and the 2022 general elections. Dobbs led to successful efforts to save reproductive rights in Kansas and Ohio – you know, bastions of liberalism, both – and other states. When asked, all Trump ever answered was, “I did the thing – I gave it back to the states and everyone loves me for it, I don’t know why Kansas and Ohio did what they did, but they did and what of it.” His running mate gave an attempted gaslighting in his debate with the framing that “yes, the GOP hadn’t had answers on Dobbs and its immediate aftereffects, but trust us, we’ll get it right.” Of course, not helping anything in that reframing was the fact the former President stated unequivocally at the one debate he chose to do with Vice President Harris that “I don’t talk to my selection for Vice President.” From that point the VP selection was rendered null and void in this writer’s eyes. Dobbs changed the midterms but remains the biggest known-unkown of the cycle. As of writing, women make up more than half of the early voting electorate. Now, is this indicative of a blow out? No. But it’s more of an underlying factor that was its own self-persuasion event and we still don’t know its total impact. That might be a little word salad-y, but in short: Dobbs changed a lot of things and discounting its effect is to the detriment of those who do so.

The former president never had to address anything of significant import in his third attempt at running for the Presidency. The supposed air of inevitability that he spun up after the midterms helped him glide through the primaries completely unchallenged, to the point that he never took a debate stage to answer for anything in front of GOP voters. Primary debates, even those that otherwise seem useless, still help frontrunners in campaigns and expose frontrunners who don’t have what it takes to win. Trump avoiding the primary debates was brilliant in terms of maintaining his aura of invincibility, but would have led to an actual campaign at a time he wasn’t using campaign money. Beyond the primaries he never let an infrastructure be built to fight anything resembling a close race. The plan for the third attempt was the same as the plans for the first and second in that sheer cult of personality and force of will would prevail. The adage “if it ain’t broke don’t fix i,” is true – however, there were actually some serious “breaks” that were pushed aside as unimportant. There were no investments of time or money to answer the most critical problems of a third Trump run: any help in building a voter contact network of any value and never being able to provide a substantive answer to what’s after Dobbs. Despite that lack of investment, yes, this race has (and was) too close to call. But the fact remains that Trump was never fundamentally favored. Why? Sheer dumb luck and cowardice.

In terms of sheer dumb luck: the President got gifts from his primary opponents generally being incompetent; and he ran the table inavoiding consequences in his various trials. Of those challengers only Nikki Haley and Vivek Ramaswamy had any semblance of a plan for a campaign, and Haley was the only one who had an actual theory of a case. Ramaswamy made himself a mercenary at Trump’s disposal to take on and take out any opponent that could pose any threat to Trump. At the debates his aim was mostly at Nikki Haley and Ron DeSantis. Why?ell, they presented somewhat credible threats to Trump. Ramaswamy used his time to take shots on behalf of Trump and was doing so in order to gain some sort of favor after his exit (though it’s debatable what he’ll get as a prize.) Haley was the sole credible challenger, and presented an actual Theory of a case and became THE outlet for Republican dissatisfaction of Trump in the primaries. It wasn’t enough to displace Trump as the nominee (and this would be a much worse race for Democrats had she prevailed), but it’s not unnoticed that the theory she presented as a need for a new generation in leadership was heard by the Democrats and manifested in the change in candidate from Biden to Harris. Trump could hold this theory in a Republican Primary, especially in a primary he effectively wrote the rules for by controlling the RNC. And it wasn’t a concern before Harris – but it should have been givenurther thought after Harris became the nominee for the Democratic Party. Now, the trials were generally dumb luck, especially in Georgia. There’s no other way to put it.

Onto cowardice: Donald Trump benefited from the lack of serious questioning in a primary setting, and from the Press ever since he first announced. Press outlets fear Trump for justifiable reasons (shooting at local papers), but they laid down time and time again. At the outset, it was for ratings and the spectacle of his rallies. Later, it was gaslit into “equal time” and equivocation, especially from the print media, as at the end of this campaign cycle we saw a number of high-profile papers reject the recommendation of their editorial boards and endorse Harris out of fear of retribution had Trump lost. It was always cowardly. Trump benefited from cowardice like no previous presidential aspirant in history.

In total, Trump never had the fundamentals of a campaign, and he never had the fundamentals for a changed race in August. Since that time, none of the fundamentals we think of for a presidential race favored Trump. He skated by on his own hubris and that of his campaign, and on the lack of courage to call him out. Trump ran a bad race in total. The extreme polarization in the electorate is the only reason it ended as close as it did.

State of Play: New Hampshire

[note: due to my own buffoonery, I’ve had this one done for a while but forgot to schedule it. So it’s publishing out of order. Obviously, it was supposed to go between South Carolina and Virginia.]

This is the second state in our series that looms large in presidential primary contests – but unlike South Carolina, it has also spent time recently as a swing state. It’s worth remembering that for all the talk of Florida in 2000, Gore would have carried New Hampshire that year if a third of Nader’s voters opted for him instead, and its four electoral votes would have given him 271 and the presidency.

2004 marked something of a turning point. New Hampshire was the only state that swung from Gore to Kerry, beginning a streak of five Democratic wins in a row here. John Lynch won the first of four two-year terms as governor that year – the only Dem in the state’s history to do so. Democrats flipped one of the Senate seats in 2008 and the other in 2016. The two Congressional seats went back and forth for a few cycles before settling into a Democratic groove. Both houses of the state legislature are GOP-held but narrowly; the executive council remains swingy.

Click to continue reading.State of Play: Georgia

The Presidency: 16 electoral votes

Georgia has made the journey from the old Democratic Solid South of the post-Reconstruction era to the mostly-solid Republican era of the post-Civil Rights era South to a highly-competitive era where it ranks in that most exclusive of categories: the modern presidential swing state. Republicans continue to dominate the Congressional and state legislative ranks thanks to maps they drew for themselves, but Democrats are back in contention for statewide races. They flipped two U.S. Senate seats in 2020 (technically January 5, 2021), one of them for an unexpired term that necessitated another election two years later. Dems won that one too, with Rafael Warnock earning a full term in a hotly-contested race with ample national attention. And of course, in 2020 Joe Biden became the first Democratic presidential nominee to carry Georgia since Bill Clinton’s 1992 victory.

State of Play: New Jersey

The Presidency: 14 electoral votes

Every four years, with rare exceptions, Republicans suggest that New Jersey is in play for the presidency. The Bush campaign did so in 2004. McCain did so in 2008. A Romney surrogate did so in 2012. And lo, the usually-demure Donald Trump upheld this time-honored tradition in 2016 and again this year. In reality, no Republican has carried New Jersey in a presidential election since George H.W. Bush did so in 1988. He came close in 1992 and his son substantially reduced the Democratic margin in 2004 in the aftermath of the 9/11 terror attacks, but the streak remains intact.

State of Play: Pennsylvania

The Presidency – 19 electoral votes

This is, of course, the big one. Pennsylvania’s far from the largest state, with its 19 electoral votes representing a steady fall from its peak of 38 in the 1910s and 1920s. But it’s the largest of the seven close swing states. We can debate how competitive Florida and Texas are this cycle, but it’s clear that a Kamala Harris victory in those states would be icing on the victory cake. Pennsylvania, though, is on a knife’s edge as it was in 2004, 2016 and 2020.